I’m Listening to Everything Composed by Arcangelo Corelli

August 11, 2013TITLE: Concerto No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6, No. 1

Composer: Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713)

DESCRIPTION OF THE PIECE:

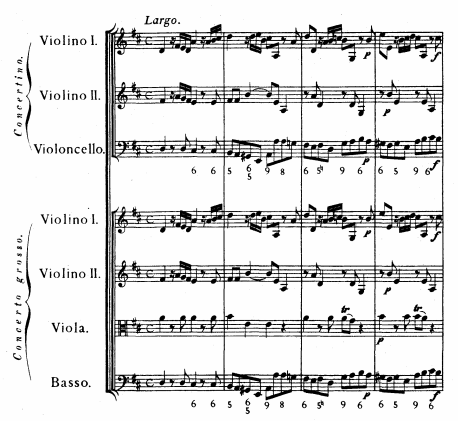

As you look at the first page of the score (above) you can notice a few things right off the bat that let you know this was composed in the Baroque Era. One is that it is a concerto grosso, or in other words, a concerto that features more than one soloist. In this case, you can see the bracket labeled “concertino” which indicates the soloists. The lower few staves show what the rest of the orchestra is made up of—mainly strings and harpsichord. These are all things that are typical of the Baroque Era. Yes, the genre of concerto grosso still exists to this day, but its heyday was during the Baroque. And the presence of a harpsichord in a piece of music indicates the Baroque Era well over 90% of the time.

“But wait,” you might say, “there’s no harpsichord indicated on the orchestral score!” Yes there is. Look at the bottom stave—the one labeled “basso.” See those little numbers underneath? Those numbers indicate the types of chords the keyboard player should ADD to the bass line. In the Baroque Era, the keyboard player read off the double bass part and improvised chords that went well with the bass line. At some point, composers started helping the performers out by providing suggestions of which chords would sound best. This shorthand is called “figured bass.” And it’s a dead giveaway that the piece is from the Baroque Era.

Full disclosure: I used to be bored by Baroque music, but over the years, as I’ve studied the composers, art, and architecture of the time period, I have discovered the vibrancy and life found within Baroque music. There’s a crisp quality to Baroque music. And the knowledge that the keyboardist is usually improvising adds a sense of freshness to any performance.

So now lets look at the title: Concerto No. 1 in D Major, Op. 6, No. 1. We can infer that this is the first concerto he wrote (Concerto No. 1), but then the ending of the title can be somewhat confusing—Opus 6, No. 1. What does that mean? “Opus,” for the uninitiated, means “work,” as in, “work of art.” So it is his sixth work, but his first concerto. AND the “no. 1” after “op. 6” means that there are multiple concertos that are all categorized as Opus six. In fact, Corelli’s Opus 6 has twelve concertos, all labeled with “opus 6” (“Opus 6, No. 1,” “Opus 6, No. 2,” “Opus 6, No. 3,” etc.).

This one (No. 1) has seven movements all quite short.

Movement one: slow stately music featuring the full orchestra.

Movement two: Fast imitative polyphony between the two solo violins while the solo cello goes crazy with sixteenth notes underneath alternating with brief adagio sections with the entire orchestra.

Movement three: A beautiful slow harmonized melody stated by the two solo violins while cello provides the bass with the harpsichord playing the figured bass. I was particularly pleased that, when the solo violins’ opening material returned a second time about halfway through the movement, they improvised extra notes so that the repetition wouldn’t come across as boring (another common practice in the Baroque Era).

Movement four: No solo sections. Just fast, bright, arpeggios played by all the violins.

Movement five: The longest movement at about four minutes. I am particularly fond of the moments when the three soloists are joined by the rest of the orchestra. There’s a melancholy sweetness to the solo sections and a richness and warmth when the full orchestra joins in.

Movement six: This movement begins with fairly obvious imitative polyphony (very much like a “round”) and continues the imitation throughout the movement.

Movement seven: Fast and virtuosic, a fitting ending for any concerto.

HIGHLIGHT: I guess I’m just a sucker for slow movements. I feel that emotion is often easier expressed through slow tempi than fast. In this particular work, I preferred movement three more than any others. My second favorite movement is the fast and vibrant movement four. In any event, listen to this work! It’s definitely a quality composition and it’s only ten minutes long!

OTHER HIGHLIGHT, NOT DIRECTLY RELATED TO THIS COMPOSITION, BUT DEFINITELY RELATED TO CORELLI:

When my wife and I were in Italy a few weeks ago, I wanted to visit Corelli’s tomb in the Pantheon in Rome. The Pantheon is an astounding edifice. Constructed by the ancient Romans over 2000 years ago, it was turned into a Catholic church in the year 609. Upon seeing it for the first time, I really felt as though I had gone back in time. There’s no way to experience it vicariously—you simply have to go there. Nevertheless, here’s a pic of my wife and the Pantheon:

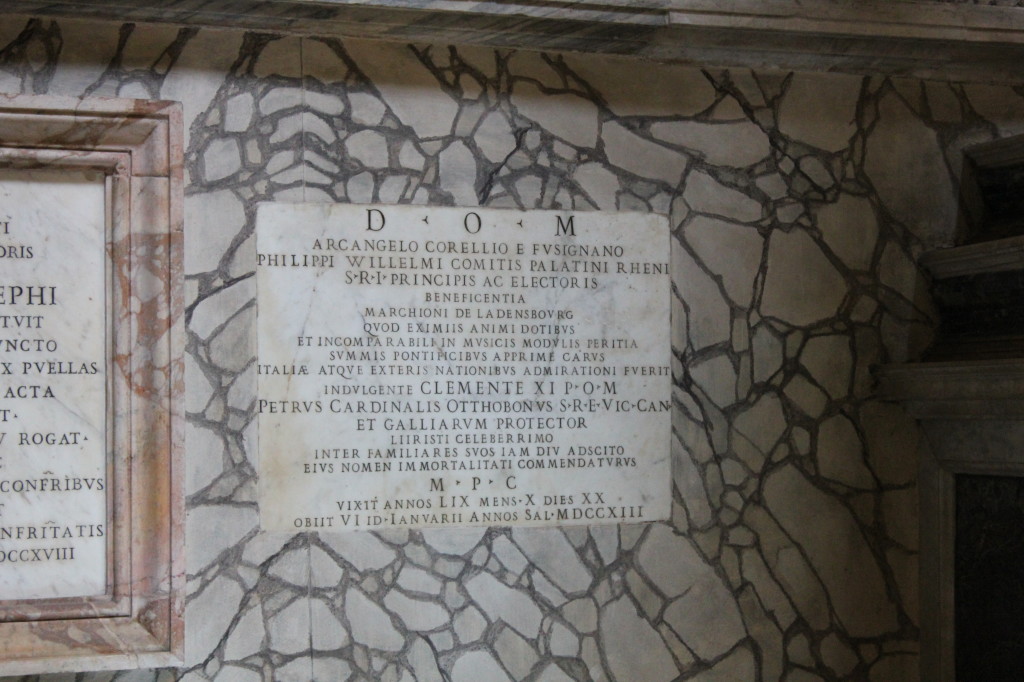

When we walked in, we discovered that we had a very short time because a church service was going to start soon, at which point they make all the tourists vacate the church, so I quickly asked a worker where Corelli’s tomb was. She was very kind and showed me that, unfortunately it was fenced off due to restoration work. I was quite sad about that, but she said, “Let’s go see if we can still see it.” She walked to the fenced in area and there was a small gap between the wall and the fencing so she leaned way in and said I could see it that way. Instead of leaning in, Jane and I squeezed past the fencing and went right in! The first pic is me with the tomb behind me. The second pic is a close up of the tomb so you can see Corelli’s name.

WHAT’S LEFT TO LISTEN TO BY CORELLI?: Actually not a lot. He only had six opus numbers! His first five opus numbers are sonatas and each opus number has 12 sonatas within it. So there are about 80 total pieces of music attributed to Corelli. I suspect I’ll actually succeed in listening to everything by Corelli a lot sooner than the other composers I’ve begun!